On July 16, capital markets went through a period of whipsaw trading as speculation emerged that President Donald Trump might “fire” Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. Later that day, the president stated he wasn’t going to remove Powell unless he found “cause.”

Do the cost overruns tied to renovations at the Federal Reserve building in Washington constitute “cause”? That seems like a stretch.

Nonetheless, questions have now resurfaced about Powell’s standing at the Fed. It’s well understood that the Trump administration would prefer the Fed to lower short-term interest rates, citing the federal deficit as a primary driver. It’s also likely that officials are aware of how the markets might respond to a Fed chair being dismissed—an act that could raise concerns about the Fed’s independence from the political theater that surrounds Washington.

If the president were to act on such an excuse, markets could react swiftly—and perhaps with good reason. The U.S. dollar serves as the foundation for most functioning global capital markets. Participants operate under the assumption that monetary policy is guided by the Federal Reserve, not directly by political influence. A change in that perception could have real consequences.

Global investors don’t respond well to surprise or abrupt shifts. Should the Fed chair be removed, risk-based assets would likely decline, while longer-duration Treasury yields could rise. The dollar might face pressure in foreign exchange markets, as central banks around the world look to reduce their exposure to U.S. assets in favor of interest-bearing alternatives—possibly including gold. The dollar’s status as the dominant global reserve currency could come under increased scrutiny.

And while the fall in U.S. asset prices may be short-lived, the initial reaction could still be significant.

History Lesson: We’ve Been Here Before

It isn’t unusual for U.S. Presidents to voice opinion about Federal Reserve policy. President Lyndon B. Johnson, for example, pressured Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin to keep rates low while promoting his “guns and butter” program—simultaneously funding the Vietnam War and expanding domestic social spending.

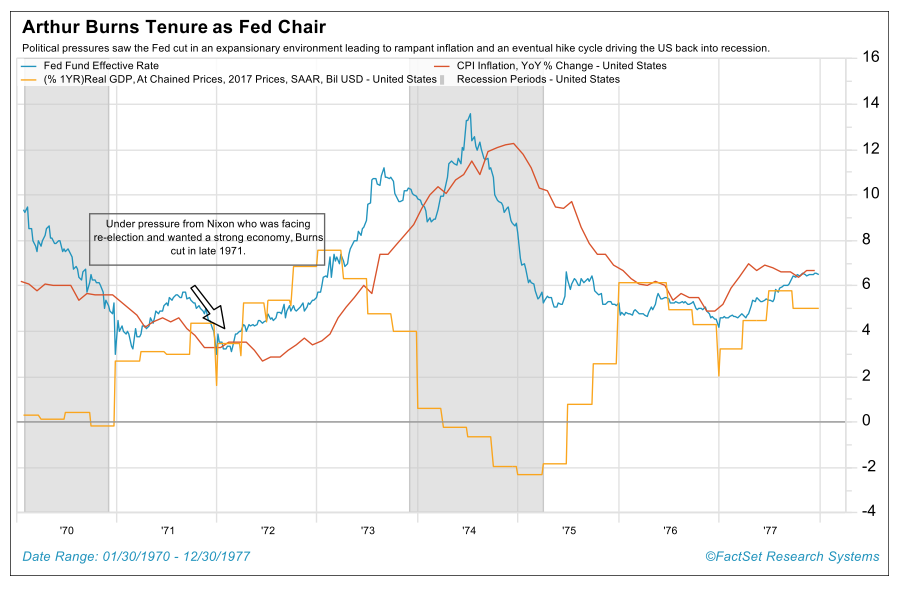

President Richard Nixon took a similar approach with Arthur Burns as Fed chairman in 1970. Burns, known on Wall Street as an inflation fighter, catered to Nixon’s desire to keep interest rates low heading into the 1972 election—even when inflation was starting to ramp up.

Those policy decisions led to the monetary-induced and oil-embargo irritated inflation spike of the 1970’s. In the wake of that experience, future presidents—Ronald Reagan among them—refrained from publicly criticizing the Fed, much less threatening to “fire” the chairman. It seems Trump has not studied monetary history—or perhaps doesn’t care about the consequences.

Are Rates “Too” High?

So, let’s take a look at why some in Washington believe the Fed is running too “tight” of a monetary policy. They argue that U.S. Treasury interest rates are almost 200 basis points higher than German bund rates and attributes this gap to the Fed keeping short-term rates elevated.

The chart below shows that the U.S. 10-year rate is 166 basis points above the German 10-year Bund rate. So, on that point, President Trump’s assessment appears to be directionally accurate.

Much of the spread between German and U.S. government bond yields can be placed not at the Fed’s feet, but at the feet of policymakers in Washington—across both political parties.

Note the chart above, which compares U.S. and German 10-year government bond yields going back to 2008. As shown, both government bond yields were in the same range until 2011. Then, a notable shift occurred: Standard & Poor’s downgraded the U.S. credit rating from its long-held AAA status. Germany, meanwhile, retained its AAA rating. Yields started widening, as global investors assessed that U.S. government deficit spending had reached a point where U.S. government debt shouldn’t continue to carry the “AAA” quality badge.

The yield spread between U.S. and German bonds was created by excess government spending—approved and supported by politicians on both sides of the aisle in Washington. This is an issue of excess government largesse and has little to do with Fed policies.

To better understand the current rate environment, we can take a look as to where “real” 10-year rates are trading, in relation to historical norms. Over the long term, the 10-year Treasury has yielded 1.7% above inflation (CPI) on average. Currently the 10-year Treasury “real” yield is 1.74%, in-line with longer term history.

So, from a “real” standpoint, U.S. government yields aren’t “too high.” The spread between U.S. yields and others reflects several factors—one of which is credit quality differences largely shaped by political decisions, not central bank policy.

Dual Mandate

Most know that the Federal Reserve has two key mandates, which tend to be contradictory to one another. The first is to maintain price stability, while the other is to promote job creation. The first mandate is aided by lower final demand growth—fostering low inflation pressures. The second mandate is aided by strong final demand growth, which drives economic growth and job creation. This creates an ongoing balancing act for the Fed.

With this in mind, which side of the balancing act should typically receive greater emphasis?

From a historical standpoint, most central bank’s mandates have viewed the maintenance of price stability as the “prime” (and in some cases the sole) operating objective. For example, the European Central Bank, following the example of Germany’s Bundesbank, states their primary objective is “price stability,” while the secondary objective is to “support government’s broader economic aims.” Similarly, the Bank of England—the U.K.’s central bank, established in 1694—states that its primary objective is to promote and maintain price stability.

There are fundamental economic reasons why the main monetary objective of a central bank is to promote price stability. Monetary policies can affect inflation pressure more effectively than government fiscal policies, while fiscal policies are able to affect economic growth and job creation—at least over a short period. The downside to monetary policy attempting to affect job creation is the risk of higher inflation, which frustrates the “main” mandate.

Where Do Things Stand Today?

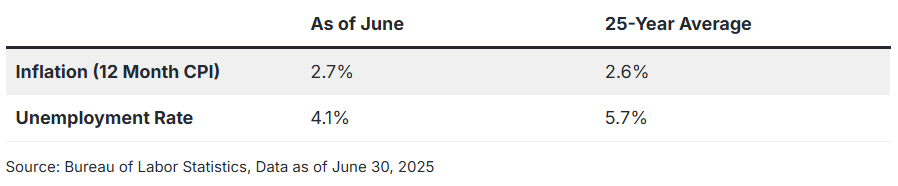

Let’s look at current data in the context of historical norms:

As noted above, the current inflation rate is “on-top” of inflation over the last 25 years, indicating the Fed’s current policy isn’t too “tight” by historical standards.

On the other hand, unemployment data show the current job market is stronger than it has been in more than two decades, suggesting the underlying economic growth profile is already robust.

Bottom line? Based on historical standards, the Fed is justified in keeping rates where they are, given the current environment relative to long-term norms.

Final Word

President Donald Trump has stated that mortgage interest rates will come down if the Federal Reserve lowers the federal funds rate. Maybe. But one of the primary influences on long-term yields—like those tied to home loans—is investor expectations around future inflation and has little to do with changes in overnight lending rates.

If the Fed lowers rates due to perceived political pressure, it is possible that longer rates will actually increase. Investors in long-duration assets might lose confidence in the Fed’s willingness to stay committed to fighting inflation.

As outlined in this work, the Fed is well-justified to maintain interest rates where they stand. History offers lessons from the Johnson and Nixon administrations about the risks of pressuring the central bank. I suggest that President Trump take these lessons and leave the Fed alone.

Chairman Jerome Powell’s term ends next year. At that point, the president will have the opportunity to appoint a new chair. It’s worth remembering that Powell was first nominated by President Trump during his previous term—he is, in that respect, already the president’s own selection.

This commentary is provided for informational and educational purposes only. As such, the information contained herein is not intended and should not be construed as individualized advice or recommendation of any kind.

The opinions and forward-looking statements expressed herein are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. The information provided herein is believed to be reliable, but we do not guarantee accuracy, timeliness, or completeness. It is provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

There is no assurance that any investment, plan, or strategy will be successful. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results, and nothing herein should be interpreted as an indication of future performance. Please consult your financial professional before making any investment or financial decisions.

Investment advisory services are offered through Investment Adviser Representatives (“IARs”) registered with Mariner Independent Advisor Network (“MIAN”) or Mariner Platform Solutions (“MPS”), each an SEC registered investment adviser. These IARs generally have their own business entities with trade names, logos, and websites that they use in marketing the services they provide through the Firm. Such business entities are generally owned by one or more IARs of the Firm, not the Firm itself. For additional information about MIAN or MPS, including fees and services, please contact MIAN/MPS or refer to each entity’s Form ADV Part 2A, which is available on the Investment Adviser Public Disclosure website (www.adviserinfo.sec.gov). Registration of an investment adviser does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

Material prepared by MIAN and MPS.